Dear Readers,

Later this week, on August 6, the Monetary Policy Committee of the Reserve Bank of India will unveil its latest monetary policy review. Typically, these reviews happen once every two months — although there have been times (as it happened in March 2020) when the RBI has decided to react outside this set cycle; it did so to counter the adverse impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic.

In each such meeting, there are two key questions that the RBI evaluates. One, what is the outlook on economic (GDP) growth and, two, what is the outlook on retail inflation.

There is one very important difference between these two concerns though. The RBI is legally mandated to keep the inflation rate between 2% and 6% but there is no such requirement when it comes to GDP growth.

In other words, the RBI is required -- by law -- to ensure that the rate at which retail prices increase in the country neither falls below 2% nor goes beyond 6%. However, when it comes to GDP growth, the RBI is not bound by any such target. It is another matter that as a statutory body — that is, as a body that owes its existence to a law made by Parliament — the RBI has to respect the wishes of the government and share its concerns when it comes to economic growth.

So here’s the thumb rule for RBI: If inflation is within the desired range, it tries to do whatever it can to boost economic growth.

Typically, boosting economic growth translates to reducing the interest rate that RBI charges to lend money to India’s commercial banks; this rate is called the repo rate. By doing so, it tries to make it easier for all economic agents (especially businesses) to seek new loans and boost economic activity. Here’s a more detailed explainer on this.

But what happens when inflation is either too low (rarely happens in a fast-growing economy such as India) or too high (as has been the case for the most part since November 2019)?

When inflation is too high, the RBI typically increases the interest rate, thus incentivising consumers to keep their money in their bank accounts (instead of spending it) while also making it costlier for businesses to take out new loans. If the retail inflation is too low, it suggests weak economic activity and one would expect the RBI to lower interest rates to boost GDP.

The odd thing with the RBI policy lately is that India’s GDP growth has been stalling even as the inflation rate has spiked. Of course, the RBI cannot boost growth as well as curb inflation at the same time. If it chooses to boost growth when inflation is also high, it runs the risk of further fuelling inflation. About inflation, the key thing to remember is that it hits the poor the hardest.

Up until now, faced with this impossible choice, RBI has favoured boosting GDP growth over containing inflation.

Read this piece to understand why it has done so.

For a while now, the RBI has hoped that the current run of high inflation in India would just be a temporary phenomenon, and that, as supply chains recover from the Covid disruption, the rate of increase in prices will subside.

But as was explained in the piece above, inflation has continued to stay high. As such, one would expect the RBI to raise interest rates and signal a shift in its stance.

However, this will likely not happen when the MPC members meet this week, and the RBI will continue to maintain a status quo on the repo rates.

Why?

Because economic growth worries continue to persist.

As against the expectations at the start of the financial year, the GDP growth in the first quarter of this financial year (April, May and June) has been underwhelming. Worse, there are good reasons why this trend is likely to spread right through the year.

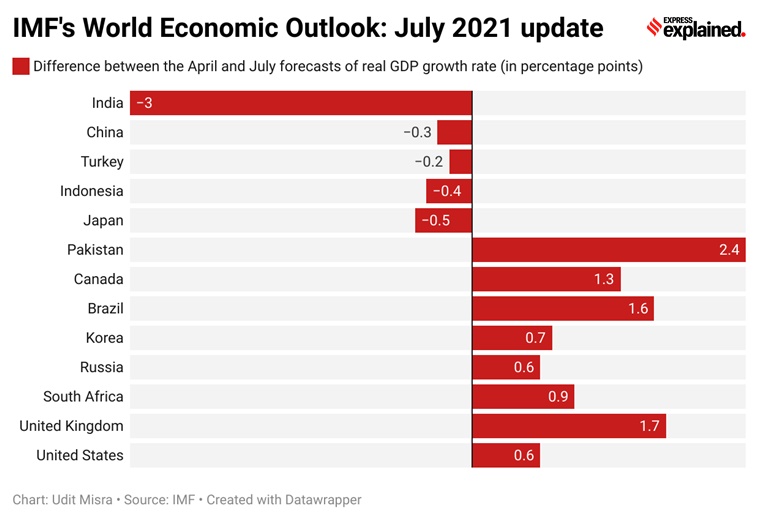

Take, for example, the latest update on the global economy by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) released last week. The standout news in IMF’s World Economic Outlook update, at least from an Indian perspective, was that between its April report and the July one, the IMF cut India’s GDP growth forecast for 2021-22 (or FY22) by as much as three percentage points. In April, IMF expected India’s real GDP to grow by 12.5% this year; in July, it revised that forecast to just 9.5%.

See the chart below, which gives the difference between the April and July projections for some comparable economies, to understand how significant this cut is. The hit to India’s GDP is the biggest among the large economies.

IMF’s World Economic Outlook: July 2021 update

IMF’s World Economic Outlook: July 2021 update

While it is undeniable that the second wave disrupted India’s growth recovery, it would be a mistake to blame it in isolation. For one, India did not go into a nationwide lockdown during the 2nd wave the way it did in April and May last year (2020).

In fact, the IMF points to two broad sets of reasons why it dialled down India’s GDP growth forecast.

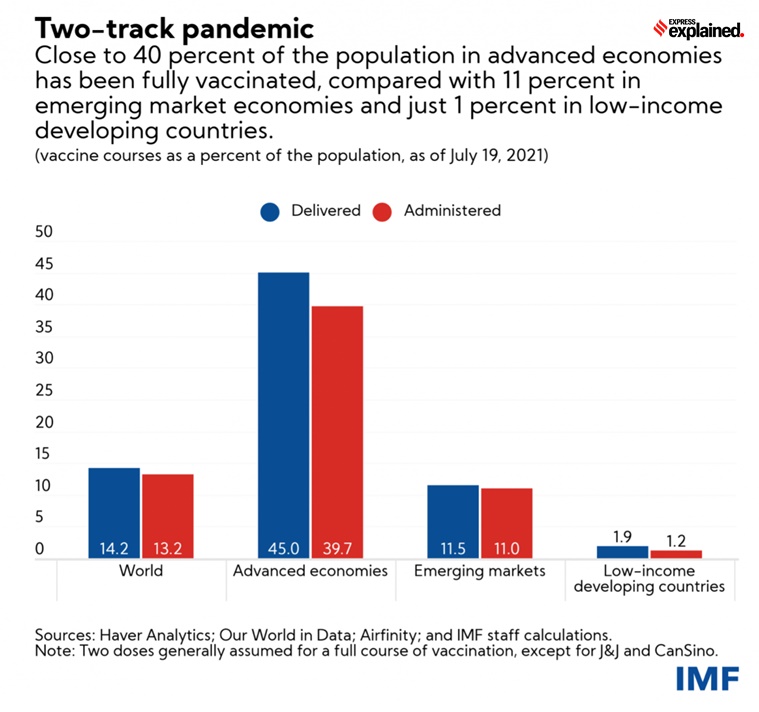

The first is the inadequate levels of vaccination. See the chart below, which points out how emerging economies such as India have only 11% of their population fully vaccinated — far behind the 40% mark for advanced economies such as the US and UK.

Emerging economies such as India have only 11% of their population fully vaccinated

Emerging economies such as India have only 11% of their population fully vaccinated

Simply put, even though in absolute numbers India has vaccinated a lot of its residents, the chances of another wave (and its severity) will likely depend on the percentage of people vaccinated — a metric in which India lags far behind.

“Faster-than-expected vaccination rates and return to normalcy have led to upgrades, while lack of access to vaccines and renewed waves of COVID-19 cases in some countries, notably India, have led to downgrades,” wrote IMF Chief Economist Gita Gopinath in this regard.

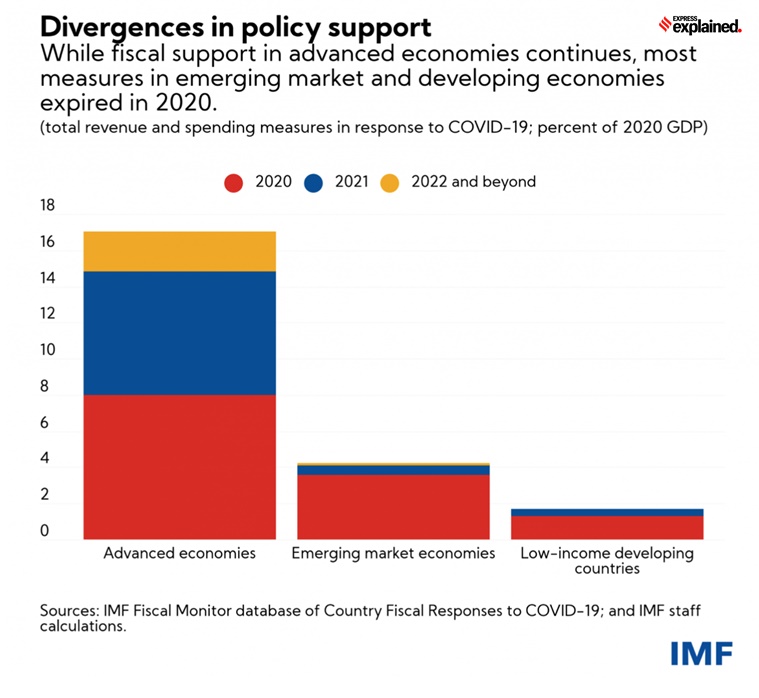

The second key factor is the kind of policy support that the Indian economy has received. As the chart below shows, governments in most advanced economies have unveiled measures to support their economies longer.

Divergences in policy support

Divergences in policy support

“Divergences in policy support are a second source of the deepening divide. We are seeing continued sizable fiscal support in advanced economies with $4.6 trillion of announced pandemic related measures available in 2021 and beyond. The upward global growth revision for 2022 largely reflects anticipated additional fiscal support in the United States and from the Next Generation European Union funds. On the other hand, in the emerging market and developing economies most measures expired in 2020 and they are looking to rebuild fiscal buffers,” stated Gopinath in her blog.

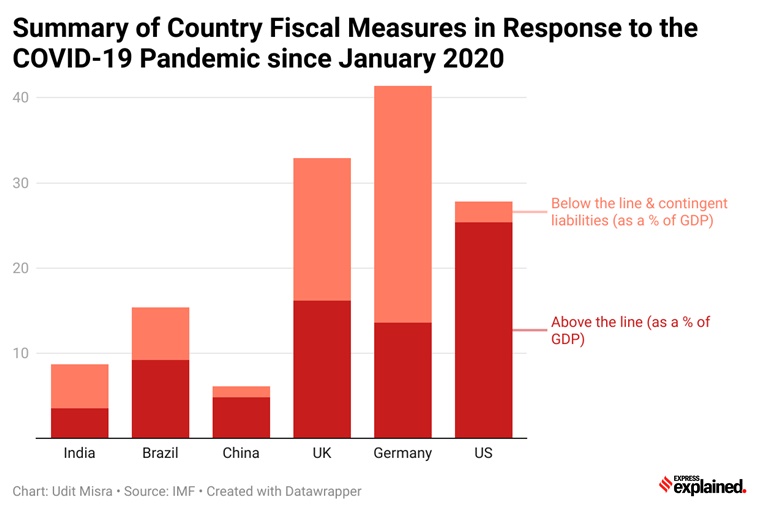

But there is yet another aspect to policy support. It is the nature of policy support. Look at the chart below, which details how the governments of some of the comparable economies provided policy support.

Summary of Country Fiscal Measures in Response to the Covid-19 Pandemic since January 2020

Summary of Country Fiscal Measures in Response to the Covid-19 Pandemic since January 2020

The “Above the line” measures refer to those fiscal decisions that boost economic activity by either increasing government expenditures (such as expanding MGNREGA or subsidised food programmes or health facilities etc.) or reducing government revenues (by providing a tax cut or any such relief to consumers and businesses etc.).

The “Below the line” measures refer to those policy decisions where instead of a direct immediate outgo from its coffers, the government (including the RBI) provides more loans and credit guarantees.

As the chart above shows, the Indian government has favoured the “below the line” measures instead of the “above the line” measures.

This is contrary to the suggestion of many economists who argue that the Indian economy is in dire need of increased direct spending by the government. That’s because in a wide-ranging downturn all other economic agents in the economy have run out of reasons to spend: Individuals have lost incomes and jobs, and firms have lost business. Government is the only economic entity that can bypass a hard budget constraint. By spending money, the government can cut down the time required by the economy to recover its long-lost momentum. If the government dithers, the recovery may be painful and slow.

In a research note dated July 19, Tadit Kandu and Prasanna A (both economists at ICICI Securities) explain the exact nature of the problem facing the Indian economy. “…employment and incomes were still well below pre-pandemic levels in March 2021, i.e. immediately preceding the second wave. Subsequently, the second wave (April-May) has only pushed back the prospects of recovery. The longer the recovery is delayed, the more difficult and less complete it would become. Prolonged unemployment bodes ill for future earnings while a prolonged drop in income weakens the outlook for future spending. Even as the economic hit due to the second wave was muted compared to last year, it also implies that the bounce-back would be shallower. Further, it is plausible that due to the extensive human toll of second wave, consumers – even from the richer households – may remain more cautious with spending plans. All this portends an incomplete and skewed recovery in domestic consumption post the second wave,” they write.

Of course, improved global demand will boost exports and higher infrastructure budgets will boost domestic economic growth. But, they conclude, “absent a near-universal fiscal support, household employment, incomes and consumption are set for a protracted and halting recovery”.

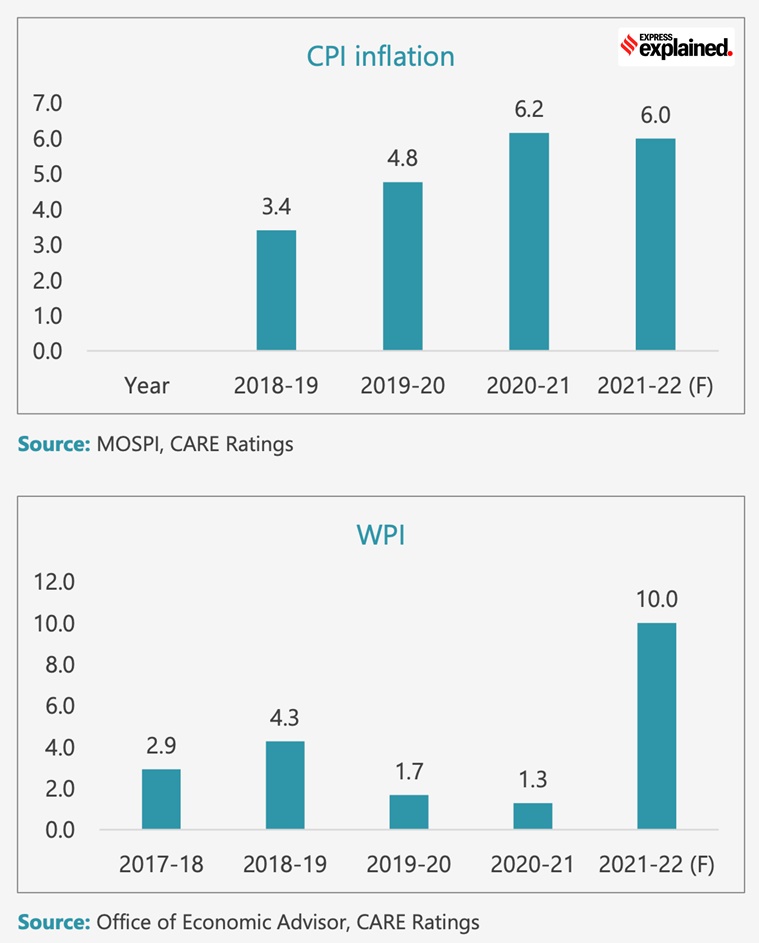

The upshot: It is true that retail inflation, which is the primary target of RBI, is expected to stay outside or almost outside RBI’s comfort zone in 2021-22. CARE Ratings (see the chart below), for example, expects retail inflation to be 6% and wholesale inflation to be 10% this year. Still, RBI is unlikely to raise interest rates on August 6 because India’s economic recovery continues to be quite iffy.

CPI inflation

CPI inflation

Share your views and queries at udit.misra@expressindia.com

Get vaccinated and stay safe.

No comments:

Post a Comment